Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature, by Mark Tercek and Jonathan S. Adams

Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature, by Mark Tercek and Jonathan S. Adams

When I asked our global sustainability

director how I could learn about natural capital and natural infrastructure, she

recommended I read Nature’s Fortune, written by the CEO of The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Mark

Tercek.

When I read in the introduction that he’d majored in English and then lived and taught in

Japan

like I did, I was hooked. We English majors who’ve been called gaijin have to stick together! I was

fascinated to learn about his pathway into sustainability…he came into it

through the back door, with a business background at Goldman Sachs, where he created a sustainability business and began partnering with TNC and other environmental nonprofits and exploring ways to make conservation profitable. "I was a late bloomer but protecting nature became my cause and my passion."

Tercek has transformed TNC into an organization that collaborates with business instead of fighting against business. As he says, "Hard-core environmentalists can be quick to criticize organizations such as TNC when they build alliances with companies. They sometimes see such collaborations as consorting with the enemy." But Tercek saw opportunity in working with businesses, because they "control huge amounts of natural resources, often more than governments." Companies are often quicker to act than government, especially as increasing numbers of businesses realize how dependent they are on natural resources and how critical they are for their survival. "The bigger the company's footprint, the bigger the opportunity for the company to reduce its impact on the environment by changing its behavior."

Nature's Fortune is jam-packed with illuminating examples of how the world's natural resources can be put to work, preserving the environment and the supply of these resources. In case study after case study, Tercek explains how cities, counties, states, and businesses are realizing how investing in green infrastructure is the best investment they can make.

For example, back in 1996, Dow Chemical Company's facility in Seadrift, Texas needed to increase its water treatment capacity...the logical (engineering) option would be to pour concrete and build a plant, at the tune of $40 million. But an innovative engineer proposed building a wetland instead, a solution that cost a mere $1.4 million. Now the wetland treats 5 million gallons of water per day, but it also provides habitat for wildlife. Environmentalists can fault Dow as a multinational chemical company, but the fact is that these multinational companies have enormous environmental footprints. When they take steps to reduce these footprints, it benefits us all. When companies invest creatively in nature instead of building traditional infrastructure, they reap many opportunities beyond just saving money. They protect the natural resources they rely on for their business.

Or take the case of Louisiana, where floods from climate change pose increasing threats. Scientists and engineers are realizing the value of floodplains, which have been replaced with hard-constructed levies, dams, and floodwalls. But nature's own resource, floodplains (flat lands near rivers where water can overflow) relieve pressure on levee systems, reduce flood risks, and filter agricultural runoff. Hard structures alone, as we saw during Hurricane Sandy or Hurricane Katrina, are often not enough to stop rising water and can actually make flooding worse for communities downstream.

A 2009 Harvard Business Review article concluded that "the current economic system has placed enormous pressure on the planet...traditional approaches to business will collapse, and companies will need to develop innovative solutions." Further, "failure to have a culture of sustainability is quickly becoming a source of competitive disadvantage. The argument about sustainability is over."

While Tercek encourages cooperation and collaboration with businesses to protect the environment, he also appreciates the value of environmental organizations that prefer to work as watchdogs on business, commenting that the pressure they place on business partnerships results in better transparency and more successful approaches to protect nature.

I recommend this book as an excellent overview of how natural infrastructure can help organizations conserve resources, save money, and create more reliable, sustainable solutions to our changing world.

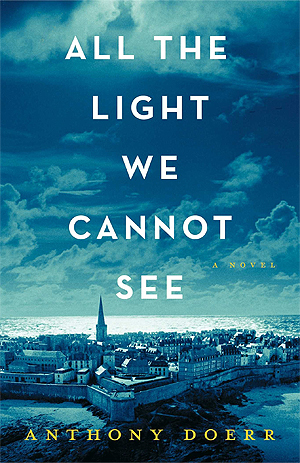

All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr

All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr